New Zealand deserves a level (default) playing field

NZ Funds recently launched a free COVID-19 KiwiSaver hotline supported by independent advisers throughout the country. The phone line is open to clients of any KiwiSaver provider and promises no sales or products, just generic KiwiSaver advice. Since its launch, the phone line has been inundated with calls from anxious investors whose savings are with large state-appointed default managers (whether or not their savings are in default funds). This raises the question: How did New Zealand end up with so many KiwiSaver members “owned” by so few managers; and is that model consistent with good customer outcomes?

One of the features of KiwiSaver, that helped get it across the line in Parliament, was that it would not be compulsory. The compromise was, and still is, that new employees are invested by default and need to opt out. While a compulsory savings regime – like most of the Western world has – would have put New Zealand in a better position today, the opt-out scheme was nonetheless a success in that a larger number of people chose to remain invested.

As New Zealand was decades late in establishing a government-sponsored superannuation savings regime, financial literacy in New Zealand was low. To safeguard millions of first time investors who did not actively select a manager and fund, the state placed their investments in a default fund. Default funds were required to own at least 80% in cash and bonds, and up to 20% in growth assets, an excellent starting point for first time investors.

The Government selected six managers in 2006 to manage default funds for a period of seven years. These were: ASB, AMP, ING, Mercer, National Mutual (AXA) and Tower. In total, two Australian-owned financial conglomerates, one American, one Dutch and one French. And only one New Zealand-owned company, Tower.

The default providers were selected for their ability to meet a number of criteria including security and organisational credibility, organisational capability, proposed design of their default KiwiSaver scheme, administration capability, fee levels and investment capability.

While admirable, these sentiments and criteria may have missed the mark. ING was sold to ANZ, a transaction which coincided with large losses in its structured credit funds. AXA packed up shop and returned to France, selling its business to AMP NZ (which, following an unreserved apology to the regulator for failures in regulatory disclosure by AMP Australia, may now be for sale itself). Meanwhile, Tower decided funds management was no longer a core business, and sold to Fisher Funds, which in turn was sold to TSB Bank.

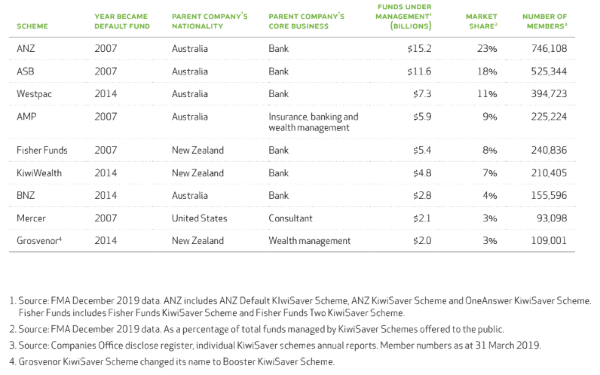

Since then, the default providers have been expanded to include two more large Australian-owned banks (BNZ and Westpac) and New Zealand’s own Kiwibank. Funds management is not the primary driver of any of these companies’ bottom line. Grosvenor is the only default provider that is a New Zealand-owned funds management specialist.

KiwiSaver managers have to meet a high standard of governance (determined by the FMA) to become a Managed Investment Scheme licence holder. Despite this, only six – and now nine – of all 23 licensed KiwiSaver managers are able to be default managers. It is time that all licensed managers be given the opportunity but not the obligation to be default providers.

The FMA’s purpose is to promote a fair, efficient and transparent market that results in good customer outcomes. State-determined monopolies are rarely associated with good long-term client outcomes. MBIE has sought feedback in preparing for a review of New Zealand’s default system. If a manager is good enough to be a licensed KiwiSaver manager, then it should be good enough to manage default funds, if it wishes to. This would give other deserving New Zealand-owned managers like: Summer, Simplicity, Generate, Juno, Milford and NZ Funds, the opportunity to do so. It would also help level the KiwiSaver playing field and go a long way toward achieving better customer outcomes.

Michael Lang is Chief Executive of NZ Funds and his comments are of a general nature.